From the original article on March 14, 2022. Author: ormulus (translator).

Translator's note: This is a translation of an article published on infobae about Disandro's life and influence on Peronism. It has a decidedly negative view on Disandro and his work, but nevertheless provides interesting information about his life and works, including letters from Perón to both Disandro and Major Alberte. We have not been overly careful to translate the text literally as we are mostly concerned with the information it contains.

Carlos Alberto Disandro was a recognized Latinist and Hellenist whose works became an essential reference point in the subjects. He seemed to be a peaceful man, immersed in his studies, but at the same time, he developed within Peronism a delusional political idea about the 'international synarchy', which lead him to create a parastatal terrorist organization.

By Eduardo Anguita and Daniel Cecchini on July 11, 2020.

“Nun huper panton agon!1” the thin man finishes in classical Greek, and the hall erupts in applause. It is a hot day in November 1966, and the Syndicate of Workers and Employees of the Ministry of Education (SOEME) of Buenos Aires province are gathered in the city of La Plata.

Few of the people present know that the phrase means “now the struggle is for all”, but they did understand the basics of the speech, which Disandro read monotonously, sometimes in an anodyne tone, over half an hour. It is about one of his essays titled “An Aborigine's Response to Toynbee”. Although he reads from the text, he gives the impression of knowing it by heart.

Arnold Toynbee was an English historian who travelled through Latin America “selling” his theory of the need for a grand agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union to save Mankind from nuclear cataclysm.

The thin man, though not yet fifty, looks older. He is a philologist, university professor of Greek and Latin, poet, essayist, and theologian named Carlos Alberto Disandro.

He is also a politically committed man who delves deeply into his favourite themes: the Homeland as the sum of Land, People, Nation, and State; its defence as a duty and right before the combined onslaught of the synarchy, and both communist and capitalist imperial powers; the spiritual continuity with a West that is Hellenic, Catholic (preconciliar) and respectful of the Hispanic tradition; and the imperative need to fight by all means against the furtive invader who attempts to conquer “the youth, the training institutes of the armed forces and the intellectual and religious strata.”

For Disandro, as he writes in his essay, the power of the United States constitutes a pseudo-empire, whose capitalist plot seeks technocratic rulership over the old and crumbling works of liberalism. The Soviet power, in turn, is another pseudo-empire, whose socialist-communist framework has been built on the disastrous results of iniquitous wars and sinister plans.

The Soviet Union and the United States are veiled invaders that threaten the Nation. That is why he cries out, without losing his monotone voice:

Total war against the invader, consolidation of the entitative Justice of the Nation, establishment of a foundational State, forged by Argentines, with the joyful consecration of the Argentine land.

Once the lecture is over, a few people, almost all of them young men in khaki shirts, go up to the skinny, aged man, who – evidently not much given to displays of affection – thanks them with a slight nod of the head and a quick handshake.

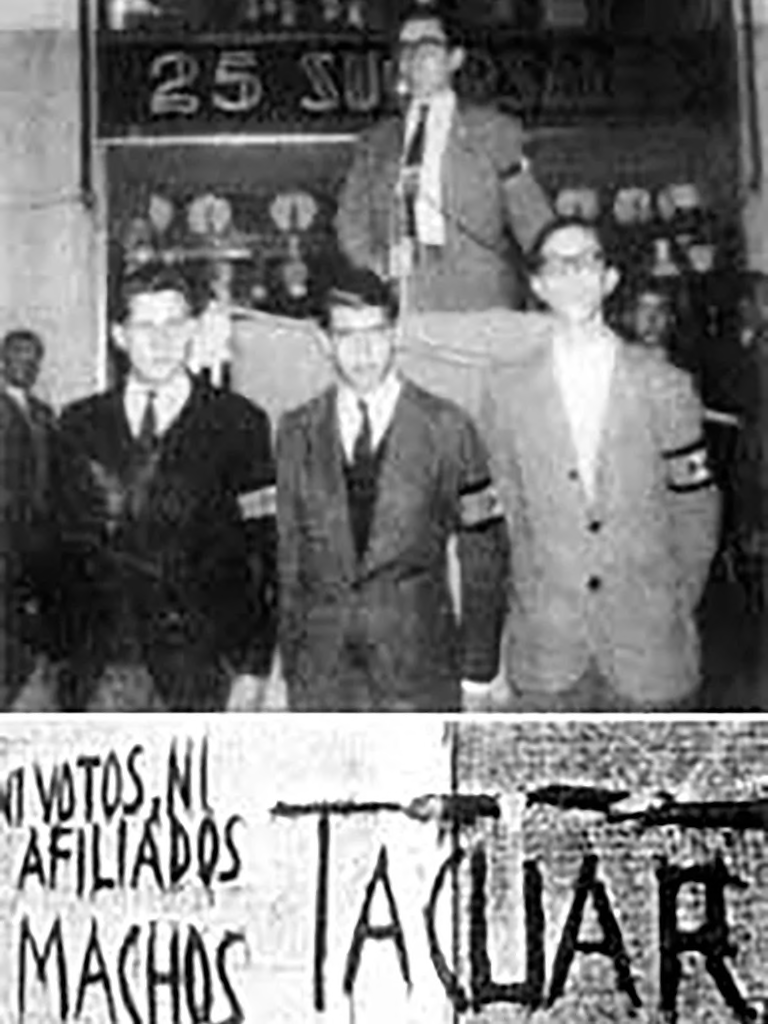

Amongst those who go up to the table is Patricio Fernández Rivero, a prominent member of the nationalist group Tacuara, and student of Literature. There also is Félix Navazzo, harmless-looking with his metal-framed magnifying lenses, but a man of action.

In a few years, these two men would transform into killers at the head of a sinister group of the Peronist far-right, the Concentración Nacional Universitaria (CNU), which would play a bloody role in state terrorism prior to the 1976 coup.

The enthusiasm of these two young men, and of many others who have listened to their words, is heightened by a fact which excites them: their teacher is preparing his suitcases for a visit to the Justicialist leader in exile in Madrid, Juan Domingo Perón. The general – through his delegate, Major Bernardo Alberte – has let him know that he is willing to listen to his ideas.

Carlos Alberto Disandro was born in La Plata on August 26, 1919, but he studied at the traditional Monserrat School in Córdoba, where he met the philosopher Nimio de Anquín, professor of Logic and Ethics. A notable representative of Cordobese Catholic integralism, in 1936 de Anquín founded the National Fascist Union to fight against secularism, liberalism, and university reformism. For him, nationalism, “promotes the guidance of the Nation… by order and unity, brought together in authority.” A staunch enemy of liberal democracy, he affirms that the Argentine State cannot take on a democratic form because this would imply a self-destructive crisis and the abyss of anarchy or – even worse – of communism.

With this ideological baggage in tow and having already finished his bachelor’s, Disandro returned to La Plata, where he graduated as a Professor of Literature at the UNLP (National University of La Plata). After obtaining his doctorate, he was appointed Professor of Classical Languages in 1947, receiving his PhD from the hands of Colonel Perón. He also worked at the Secretariat of Labour and Social Security and was an active collaborator in the process of university reform that culminated in the Law 13.031 in 19472.

Laid off in the so-called Revolución Libertadora in 1955, Disandro took refuge in his intellectual work, which had basically three aspects: the political-philosophical pamphleteer, the literary, and the poetic.

To spread his ideas, in 1959 he founded the Cardinal Cisneros Institute of Classical Culture in an old mansion on 115th Street between 60 and 61 in La Plata, where he met with his followers and ran courses on history, philosophy, religion, and politics. He also created a magazine to spread his ideas, La Hostería Volante3, in which he published articles under the pseudonym El Bodeguero4 , and a publishing house, Montonera5, whose name he would change in later years to avoid it being confused with the political-military organization of the Peronist left.

By the mid '60s – in which time he would visit Perón in Madrid – Disandro and his followers were sure that the only way to save Argentina from the debacle of a world polarized between two blocs and in complete decay was Peronism.

The enemies it faced were powerful: not only the Soviet Union and the United States, but also Zionism and a Catholic Church ruled from the Vatican by a communist infiltrator known as John XXIII. To encompass all these enemies, Disandro lumped them together in a blurry category – “the agents of the international synarchy”.

In his essay “The Synarchic Conspiracy and the Argentine State”6, he writes that “Synarchy, according to its etymological background, means the radical convergence of principles of power at work in the world since the origins of mankind. This convergence of opposed principles of power is what indicates that we are in a new moment in the process of world government, because this has until now not occurred, neither in the Illuminist lodges of the 17th and 18th centuries, nor in the revolutions of the 19th century; it occurs instead in the 20th century, after the process of liquidation of the world wars.”

This idea was based on a characterization that presented Peronism as the anti-synarchist movement par excellence insofar as it maintained a critical stance towards and distanced itself from the colluding Soviet and North American “imperialisms”. This critical stance towards imperialism was based on a central policy of Peronism - the third position – explains the historian and researcher at the UNLP Juan Luis Carnagui.

It was these topics that he wished to discuss with Juan Domingo Perón at his residence at Puerta de Hierro.

The meeting between Disandro and Perón had begun to take shape in August of 1966, when the Justicialist leader sent the Latinist a carefully considered letter:

I have carefully studied your work on the latest events in Argentina “The Strategy of a Synarchic Power” and I find it excellent from very point of view I have analyzed it. For a long time now, I have also been spreading in all directions the idea that there exists a conspiracy of all the international forces that have been acting negatively towards the motives which we are pursuing and that the world that is trying to free itself is pursuing. In fact, I have already published a work, which you should know, about the Argentine situation in which I deal especially with the “Third World”7, a consequence of the “Third Position” announced by us more than twenty years ago. Your excellent work deepens the analysis and penetrates deeply into the Argentine problem, subjected to the strategy of a synarchic power.

They met twice in Madrid, in January of 1967, which allowed Disandro to develop not just his ideas but also to warn Perón about the dangers of synarchic infiltration, which, according to him, threatened Justicialism. He was persuasive enough that the exiled leader proposed that he join the “Escuela Superior de Formación Política del Movimiento Peronista” and that he head the struggle against the parts of the movement which adhered to the Second Vatican Council, convened by John XXIII and affirmed by Paul VI, two popes who, according to Disandro's judgement, were “communist infiltrations”.

In a letter which he sent shortly after meeting with Disandro, Perón tells Alberte that the general had charged the Latinist with a mission.

Perón wrote to his personal delegate:

In the letter which I am writing to Doctor Disandro along with this one, I ask him to speak with you to come to an agreement about what should be done to neutralize such actions. He has a mission which I gave him some time ago to clarify to university workers and professionals some dangerous issues that people often let pass by carelessly, such as may happen with the particular matter that I am referring to in this moment: Comisión Populorum Progressio. Anyway, you will see there: Dr. Disandro's help can be valuable because he has been after these vermin for a long time.

Upon his return, Disandro devoted himself not only to the tasks entrusted him by Perón, but also organized, with the young nationalists gathered in the Cisneros Institute, an organization which he called the Concentración Nacional Universitaria (CNU). It soon became an ultra-right-wing shock group, and under the slogan “delenda est marxistica universitas”, it was dedicated to the persecution and intimidation of militants belonging to revolutionary and Peronist organizations located to is obvious left, mainly in the cities of La Plata and Mar del Plata.

The CNU rose bloodily to fame on the 3rd of December 1971 – shortly after Disandro formally introduced it in an event accompanied by José Ignacio Rucci – when an armed gang attacked with gunfire an assembly that was taking place in the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Mar del Plata and killed one of its participants, the 19-year-old student Silvia Filler.

On June 20, 1973, its members, led by Alejandro Giovenco, Félix Navazzo, and Patricio Fernández Rivero, participated in the Ezeiza massacre8 together with other groups of the Peronist far-right, with logistical support from the Ministry of Social Welfare under José López Rega and the Federal Police.

In 1974 – after the displacement of the governor of Buenos Aires, Oscar Bidegain – the CNU placed itself under the orders of the new governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, the ultra-right-wing trade unionist Victorio Calabró, and began to operate in the province with the protection of the Buenos Aires police, which supported it with personnel, weapons, and freeing up areas for their criminal activities.

From then on, and until shortly after the coup, its task forces committed attacks, kidnappings, and assassinations under the protection of the State, in some cases conjointly with the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (AAA or Triple A).

From October 1975 it also operated under the orders of Army Intelligence Battalion 601. At the same time, its members dedicated themselves to committing common crimes aimed at gaining personal wealth and revenge. The CNU task forces were deactivated in April 1976 by order of the head of the 113th Operations Area, Colonel Roque Carlos Presti, when their actions, often undisciplined, ceased to be useful for the systematic plan of extermination put into practice by the civil-military dictatorship.

By then, the CNU had sown the cities of La Plata and Mar del Plata with bullet-riddled bodies in order to provoke terror among the population.

It is estimated the CNU committed more than one hundred kidnappings and murders between the end of 1971 and the beginning of 1976, most of them under police protection.

The Latinist and Hellenist Carlos Disandro was never charged for the ideological authorship of these crimes. With the return to democracy, in December 1983, Disandro and Patricio Fernández Rivero returned to edit the magazine La Hostería Volante, through which they established contact with various far-right publications in other countries.

Carlos Disandro died peacefully at his home on January 25, 1994, at the age of 74.

The Argentine justice system took decades to investigate and judge the crimes committed by the organization he had created.

It was only in December 2016 that the Federal Court of Mar del Plata sentenced seven of its members – amongst them the former prosecutor Gustavo Demarchi – for crimes against humanity. A year later, the Tribunal Oral Federal N°1 of La Plata, sentenced to life imprisonment the last leader of the CNU gang in La Plata, Carlos Ernesto Castillo, and acquitted his second-in-charge, Juan José Pomares, on grounds of “the benefit of the doubt”. This last sentence is in the appeal stage.

In the city of La Plata there are two memories of Carlos Disandro. Many remember him as that anodyne, thin teacher, almost a ghost, nicknamed “El Pélida”9, who bored students at the Rafael Hernández National School with his Language and Literature classes. Others remember him as the mastermind of one of the bloodiest vigilante organizations that participated in state terrorism before the coup.

1 Νυν υπέρ πάντων αγών – from Aeschylus's The Persians.

2 Also known as Ley Guardo (the Guard Law), promulgated in 1947 during the Perón's first government. It regulated higher education, and stipulated the social function of the university, and aimed to deepen student participation at university, giving students the right to vote in university affairs. It also stipulated that university rectors be appointed by the national executive body, provided scholarships, and prohibited lecturers and students from political activities at universities.

3 “The Flying Inn”.

4 The Winemaker

5 Montoneras were armed civilian paramilitary groups who organized in the 19th century during the wars of independence against Spain.

6 “La conspiración sinárquica y el Estado Argentino”, Ediciones Independencia y Justicia Buenos Aires, 1973.

7 I.e, states not aligned with either the US or the USSR.

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ezeiza_massacre

9 Achilles was called Pelides, son of Peleus.

Library of Chadnet | wiki.chadnet.org