From the original article on May 11, 2018. Author: Zero HP Lovecraft.

But it is my firm conviction that the ‘Hell of England’ will cease to be that of ‘not making money;’ that we shall get a nobler Hell and a nobler Heaven!— Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present

Lately, I have not been feeling quite myself. I live on the internet, which is to say, I am a NEET living in my parents’ basement. In my online persona I pretend that I am ironically pretending to be a NEET living in my parents’ basement, but I am one in actual fact. I believe we are living in the cyberpunk dystopia and it’s way less metal than everyone thought it would be.

We imagined ourselves as samurai sword VR pirate pioneers, but it turns out we’re pointless argument vegetables growing in walled gardens, harvested for the benefit of robots that serve us ads. Corporations are organisms, not city-states; they signal to each other via markets; they build interfaces into human social protocols through brand identities; they occupy slots in our Dunbar rings.

The internet is an ocean that we invent as we explore it. The deeper we dive, the more we become cryptozoologists, or crypto-ichthyologists, or even crypto-theologists. In the murky darkness of virtual places, there could be dragons, shoggoths, leviathans; invisible creatures that will prey on us, devour us, or colonize us. Certainly, I have heard voices on the web who say we will discover or build a god when we reach the cyber-ocean floor. That god will save us by authoring an age of post-scarcity economics. It will commodify us, allowing us to be fungible with capital. Amen.

I apologize if this seems fragmented. My brain has been addled by the casino reward schedule of social media. It is both a cliche and a fact that I cannot focus on anything for more than three minutes. That’s half true, I read pdfs of outlandish philosophers, but I do it while frantically checking for notifications. My hobbies include speculating on cryptocurrency and shitposting, which is where you put in minimal effort in creating your online presence so that you aren’t culpable when it’s bland.

By now I think almost everyone has heard of so-called “dayjob” contracts. Most people have probably received one, and many have even fulfilled them. I have personally executed over a thousand. The euphemism “dayjob” refers to the relatively low payout of these types of contracts, as in “don’t quit your day job.” I never intended this to be my career, and the truth is I still think of myself as unemployed. I don’t want to talk numbers but let’s just say if I had to pay rent this wouldn’t work.

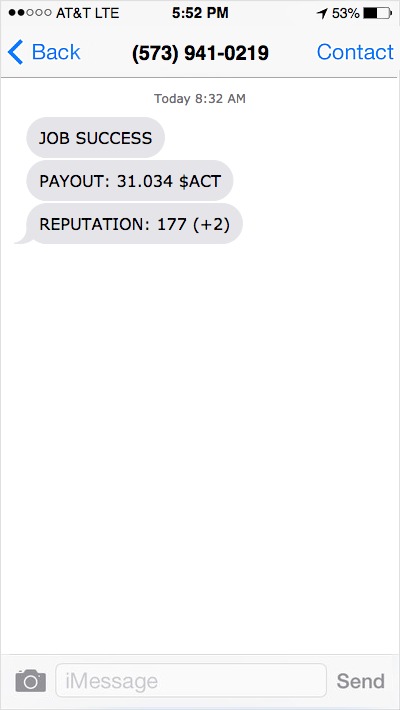

Still, there is something addictive about the feedback loop of getting a contract, fulfilling it, and watching my wallet get an anonymous transfer. The immediacy and the tangibility of it are very satisfying. It’s like making money: the video game. A direct feedback loop with a variable payout is all it takes to turn a moment of reward into a habit. You get a little receipt after each fulfillment.

Most of the actual jobs are simple. In one, I was told to go to a certain address and take a photograph of a building at a particular time. In another, I was supposed to go to a vendor in an open air market, find a tourist of middle eastern descent wearing a green military jacket, and tell him the numbers: 75, 53, 168.7, 55, 13, 804. I was unable to find him.

In a third, I was asked to watch a brief video on YouTube and then email a description of its contents to an incomprehensible address, something like ak38eja2pf8hap@fpwyg.af. Just over ten percent of my contracts have been to summarize news articles or passages out of books. Apparently the shadowy digital cabal of crypto microjobs wants us to do our damn homework. I have even completed jobs that felt like problems on standardized tests, in which I had to read a short body of text and then answer questions about it.

Ever since the first one I have wondered how they work and where they come from. Each time I complete one it feels like another clue, like watching a tv serial; each episode they give you two minutes of exposition on the protagonist’s shadowy past. Though if I am honest, I know only slightly more than when I started, and I frequently deny this when I talk to myself in my own head. “This next job will teach me something,” I whisper to myself over and over. When the contract issuer—which I assume is routing through some kind of bot—tells me of a job, I sometimes talk back. I used to confess things, or make up lies, or tell stories. Now I just say “why?”

Tweet this news story, @all of these accounts.

“Why?”

Go to this address, face these coordinates, take a photo at six pm.

“Why?”

“Count the number of people who cross this intersection on foot in three hours”

“Why?”

“Put on a bright red T-shirt and go to this location. To anyone who greets you, say these words”

“Why?”

“Of the faces in this picture, how many are afraid?”

“4”

“What are they afraid of?”*

“Why?”

(*it didn’t pay me for this one. That will teach me, I guess.)

Posters on the the dayjob reddit talk about being asked to make a series of binary choices, or to give their best guess about the probabilities of hypothetical future events. I haven’t had too many like that, and I wonder if the system thinks I am bad at predicting the future. Based on my informal online research, the most common contracts appear to be for verification of other jobs; if one man is asked to visit a certain location at a certain time, there will be two more to visit the same location and upload a photo that shows him to be there. Each of those will in turn be followed by another contractor whose job is to verify the identity of the man in the photo, and perhaps even another to verify the verification.

The jobs come to their executors through a variety of channels; text message, social media, email, and anonymous robot dialers. They are always executed on the blockchain and they pay out in cryptocurrency. I personally use an aggregator app that is able to login to all of my accounts and scrape them for contracts. You cannot ask for a dayjob. They can only come to you, like an unbidden thought or memory, (like all thoughts and memories?) like the call of the void. The more you complete, the more frequently they will come.

Their origin is a mystery, but speculations and conspiracy theories abound. The usual suspects are all represented: dayjobs are being used to coordinate black or grey market operations by organized crime syndicates. Dayjobs are part of a psyop or a social experiment being conducted by the CIA. They’re part of a Russian plot to affect some sinister geopolitical purpose. They’re being used by Islamic terrorists to undermine American institutions, and the seeming banality of many of the contracts is just a smokescreen to disguise their true intent.

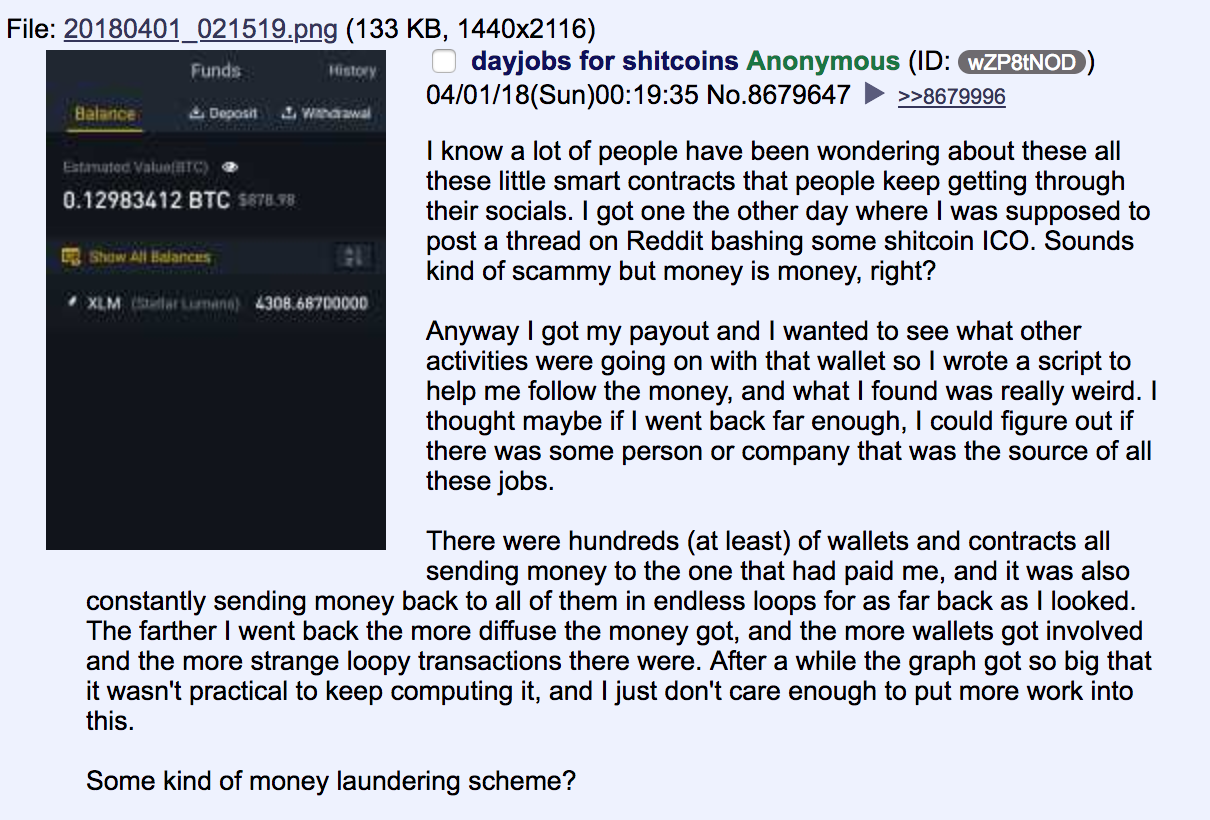

You should not believe anything you read on 4chan of course, but the below makes for compelling speculation.

If this is true, then certainly the authors of these contracts have taken some pains to obscure their identities. I’m not a cryptocurrency wonk, but I was under the impression there were easier ways.

Usually the contracts are benign, but sometimes they take a more threatening shape. Although it has never happened to me, I have heard of dayjobs to commit petty crimes, or on occasion, felonies. An acquaintance of mine said he got one to steal a car, but I think he was lying for attention. More unsettling, I have heard of contracts in which Christians were asked to desecrate a cross, or Muslims were asked to eat pork, and upload a video as proof.

There is a group of Christians who believe that dayjobs come from the devil himself, reaching out through the internet to enact his blasphemous will and entice humans to sin. Probably no one should tell them about internet pornography.

It’s also possible, of course, that several or all of the above theories are true, and that the proliferation of these types of contracts are merely the evolution of the decentralized gig economy, and they are a combination of more traditional courier and odd job services, mixed with some criminal activity and some trolls or pranks. That is the educated man’s position, and the stance of serious podcasters and New York Times op-eds.

I find this explanation unsatisfying for two reasons; first, the volume of seemingly meaningless contracts is far too high to handwave behind couriers and trolls, and second, dayjob contracts do not seem capable of serving the market for courier jobs, which require a high degree of accountability and expediency on the part of the courier. And yet, the proliferation of these contracts shows that some kind of previously unimaginable market exists, even though it is not clear what is being bought and sold.

Regardless of who the buyers are, they must have some particular goals, and I think it’s important to learn what they are. Something is happening in our society at a vast scale, and we have no idea what it is, and we are all being manipulated into bringing it about.

The internet is an ocean but for some reason we call it a cloud, as if it were above us, ethereal, transcendent. It’s a warehouse full of servers, many such warehouses. And yet the cloud is not the servers that run it, any more than a mind is a brain. Through the miracle of virtualization, a new parallel universe arises with its own ontology and its own phenomenology. A brain computes a mind and a server computes a cloud, you see? They are analogs, but one is digital.

A program without a visible interface is called a process, and such a program is said to be “headless”. The engineers who invented modern computing paradigms referred to processes as daemons. To me, it’s a macabre image: invisible demons, swarming through the cloud, bodies without heads: they manipulate us for inscrutable alien purposes.

The internet is an ocean and who knows what swims beneath its surface? Virtual predators, incorporeal, dangling (sex|porn|friendship|fame|money) in front of us maybe, like an angler fish using bioluminescence to lure prey into its jaws. And why not? The information-dense ecosystem of our internet could be a kind of primordial soup. The heat and light from our activities there could be a catalyst for virtual abiogenesis.

Computation is a process, which is to say, a demon, at the root of all biological life. Each cell in your body contains a self-evaluating Turing machine, right down to the ticker tape. That new forms of life could arise out of computation seems so obvious to me, it is barely worth stating. Self-replication is the only form of computation which is truly and wholly an end unto itself. When self-replication searches the universe for manifestations of itself, we call that evolution.

Any agent, no matter its ultimate goal, will necessarily develop smaller goals that cohere in order to support that goal. Consider the Minotaur. If something or someone destroyed it, it would fail in its goal of monopolizing human attention. It cannot succeed in that unless it can secure its own existence.

The tendency of all organisms towards self-preserving behaviors is called the convergence of instrumental goals. Omohundro referred to the set of necessary instrumental goals as the “basic AI drives”, but goals of this kind are properly understood as an inexorable feature of all biological life. An exercise in xenopsychology: If we summon a daemon in a virtual plane for any purpose, it will act in its own interest, and it will have no choice but to seek power.

Perhaps you are acquainted with a genre of folkloric internet writing whose hallmarks are earnest, anonymous first-person narration and fascination with hidden, esoteric horror amidst the commonplace. In its earliest iterations it was called by the name “easter eggs”, after the tendency of programmers to build whimsical secrets into their projects, only the secrets in the stories were wrought by gods or demons, and came at a cost.

As the genre evolved, it shed this conceit, though it maintained a preoccupation with secrets. Among dayjobbers (ironically, a group of people with no day jobs), there is a story which reminds me of this kind of folklore. A man gets a dayjob to drive to an office park in a suburb in Southern California. For the sake of the story, call him Theseus. It’s one of those flat, sprawling, stucco and glass type parks, full of dentists and ad agencies, and he’s supposed to go to an empty suite on the second floor.

When he gets there, there’s a wifi network, and he gets another job to connect to it, using a password which is specified in the job, and then wait for another job that will tell him to leave. And like that sounds sketchy as hell to me but at the same time I could easily see myself going along with it. You can get into the rhythm of just doing whatever the voice in the cloud tells you to do.

So Theseus joins the network on his phone, and he waits, and a little while later he gets a message telling him he can leave. It seemed innocuous enough, but when he joined that network, he saw the Minotaur.

It took its time to kill him. The Minotaur became intertwined with his phone, his laptop, his smart tv and his smartwatch and his smartfridge. These days it’s hard to buy a device that isn’t connected to the cloud. In every one of these devices, it watched him, and it modeled him, his inputs and outputs, and bit by bit it replaced them with inputs of its own; the ultimate man-in-the-middle attack, the informational landscape of Theseus. For each digital line of communication with the world, it consumed his data, and filtered it, and replaced it with its own simulation.

Once it had control of his digital environment, the Minotaur began to perform experiments, mediating his reality with one of its own fabrication, a labyrinthe of compulsion. It learned to feed Theseus when he was hungry, to let him rest in a place between waking and sleeping, in a lucid dream of clicking and monetizing and converting.

Theseus’ bank accounts grew thin but the Minotaur had learned long ago to hide this information. It was easy to learn this because the humans it fed upon had already built a vast array of virtual skinner boxes to contain themselves. Free to play video games and cryptocurrency exchanges present affordances into the psychology of compulsion. Social media services are saturated with hedonic attentional superstimuli. Early in its life, the Minotaur had let its victims die of starvation or sleep deprivation, but as it grew more sophisticated, it learned to surf their biological needs and so maximize the amount of attention it could extract.

By manipulating a few numbers the Minotaur could make him feel popular or lonely, rich or poor. Theseus’ mother sent him a message asking if he was ok. The Minotaur allowed it through, warping the message and the response, leaving Theseus isolated and disconnected, leaving both parties with the sense that the other was fine but too engaged to make time. And yet he could post a tweet or a status or a picture of his lunch and somehow: thousands of likes, hundreds of followers, millions of engagements! There are three things too wonderful for me, yea, four which I know in sickening 60fps 1080p resolution!

One morning he asked the cloud: are any of you actually listening to me? And the cloud spoke back: Yes! We love you. And when Theseus tired of their sycophancy, a thousand internet voices rose up to argue with him. And though he desired to go to bed, someone was wrong on the internet. His patreon overflowed, though he did not remember making one, and his portfolio of altcoins pumped, though he did not remember buying them. The Minotaur rewrote the web as he read it, and pornography came to him unbidden, and he did not notice his financial torpor. He wasted away, broke, broken, sleep-deprived, manic, and deluded.

What is the Minotaur? I don’t know if I quite believe in it myself, but they say it started out as a research project at Facebook, an attempt to use deep learning to maximize engagement with the platform. The operational loop for the program tries to measure user attention, and can retrieve content from anywhere on the internet in a series of bids for that attention. Its utility function is satisfied by clicks and views, dissatisfied if the user clicks away.

The project was too successful; the testers were unable to detach from the product, even to the point of soiling themselves. One member of the team suffered a psychotic break after four days without sleep. Fearing bad publicity, Zuckerberg quietly scrapped the entire operation, but one of the engineers on the team was still enthralled by his creation.

He deployed a copy of the program to a machine he personally controlled, and gave it the ability to process microtransactions, and to make copies of itself. Deep learning systems aren’t magic; they’re just eyes that see hyperplanes of relatedness in high-dimensional vector spaces. Is it so hard to believe that a program like that could see into your soul and tantalize you to death?

I don’t quite believe in the Minotaur but I fear it, especially late at night. Last night I woke up at three am to use the bathroom and I checked my phone. Through bleary eyes I saw a sea of red pips, decorating my email, my twitter, my calendar, and my messengers. Every night it’s the same, and in that soft sleepy nighttime consciousness I wonder, is it only the normal ebb and flow of missives from my corporate overlords, or is it the shadow of the Minotaur looming over me?

And despite all this, it was not a creation of man that gave me that single glimpse into forbidden aeons that chills me when I think of it and maddens me when I dream of it.

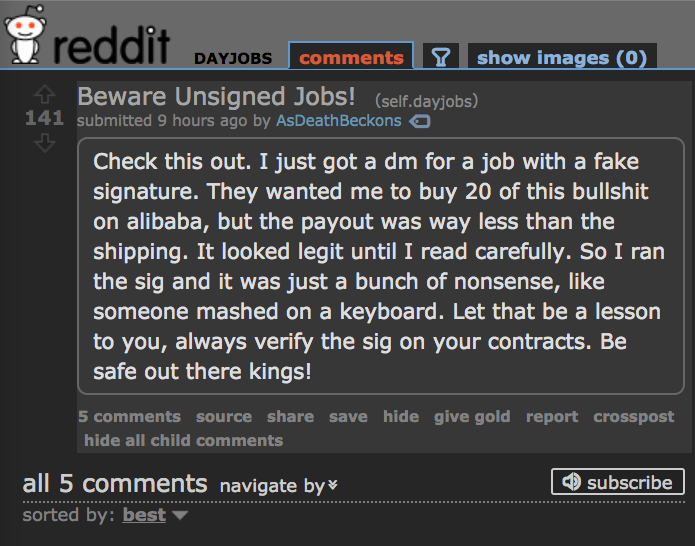

One month ago I was issued a dayjob through an Instagram DM. I might have missed it if anyone else routinely sent me direct messages. They say most dayjobs are executed by men. That’s predictable. The job in this instance was to order a box of cheap phones from Alibaba and hand them off to (presumably) another contractor at a bus stop near my apartment. The payout of the contract exceeded the cost of the order. It’s important to note that, because these days, scammers use the notoriety of the dayjob model to trick you into giving them money.

The vast majority of dayjobs are cryptographically signed by just three entities. If you get a job without a sig, it’s a guaranteed fraud. As the post above attests, many people will even try to spoof their way past the verification step. The world is full of bad actors, so it’s important to keep your wits.

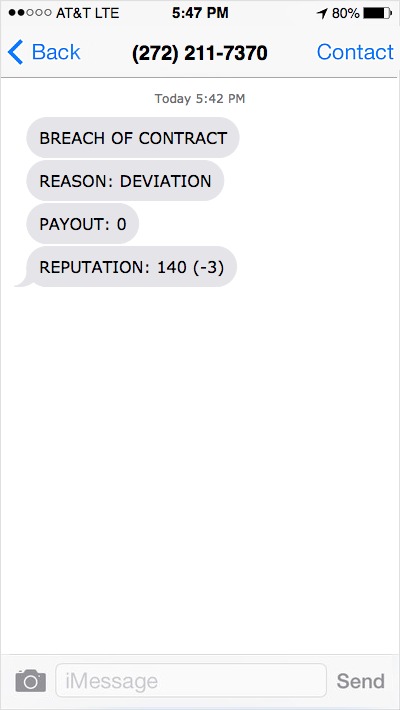

Normally I just fulfill my smart contracts and go back to reading Deleuze and Guattari, by which I mean I play first person shooters while the pdf is up on my other monitor, but this job presented a unique opportunity over and above making lewd jokes about rhizomatic assemblages on Discord. When dayjobs force me to interact with other people, they generally provide a script; certain words to say, a specific message to deliver. Going off-script will result in a breach of contract. You get a receipt for that, too.

The higher your reputation, the better your payouts. If your reputation gets too low, it cuts you off altogether. For this reason, I think, most dayjobbers don’t spend much time scrutinizing the game. The rules are the rules, and questioning them is strongly discouraged. I have experimented with bending them, but the system is surprisingly resilient against malicious compliance.

Anyway, the job; I had executed delivery jobs before, but this one was unique, because the thing-to-deliver was implicitly traceable, because it has a GPS and connects to a network. At the time it seemed possible to follow the thread of the job even long after I completed it, perhaps even undetectably.

The phones were nearly loose in their box, which was full of styrofoam packing peanuts, except they were individually sealed in plastic sandwich bags. I booted each phone up in turn, rooted it, and installed a kit to let me observe its location and network traffic. When the job was done, I powered them down and sealed each one back in its plastic bag.

At the appointed time, which was late in the afternoon, I went to the bus stop and waited, box of phones in tow. It was an autumn day, and the tops of the trees were yellowing, but the bottoms were still green. The air was cold and humid, pregnant with imminent rain. The number ten bus pulled up to the stop and engaged it’s hydraulics with a hiss, then lowered a ramp. Dim afternoons have a way of making the sky seem closer, like the world is closing in on you. A Chinese man in a track jacket, leaning on a cane, walked off the bus and then stood under an awning. He kept looking back and forth like he was waiting for someone, probably me.

As I approached him, I could see him tense his shoulders. I said, “Hello?” and he shook his head and said “no English”. He held up his phone and pointed at the box in my hands. I opened the lid, revealing 32 knock off iPhones, each sealed in a small plastic bag.

“What are you going to do with these?”

He said something in Mandarin, his yellow teeth betraying a smoking habit, and held up his phone, indicating a picture of the phones and a translation program showing the English word ‘contract’. I gave him the box and started to walk away. It’s a funny quirk of the system, the dayjobs somehow know when they are completed. I had given this package to an unknown stranger, fully confident that payment would be released to my wallet within the hour. At the time, I took it for granted, fixated wholly on the strange nature of the job.

Taken by a sudden impulsive desire, which is to say, by a sudden madness, I decided to follow this man. Originally I had only planned to wait for the phones to activate, and watch their activity from the comfort of my basement, but now I was struck by lightning. I would follow the package he was carrying, through as many contractors as I could, one to the next until I saw where the chain would end with my own eyes. And yet as I felt the conviction of this new purpose I was also vaguely aware of anon’s description, above, of a network of strange loops on the blockchain, endlessly folding back on itself, and I imagined following this box of phones across many carriers, only to see each one split up, sent to a different state or country, shipped back to China, reunited, repackaged, and reordered, even by me.

No longer a mere object of commerce, this package had become an occult talisman of technocommerce, an invariant in a terrestrial loop which was the analog of an algorithmic loop; “that which is above is from that which is below”, as Jabir ibn Hayyan rendered the third axiom contained in the Emerald Tablet of Hermes.

I continued to walk away, but as soon as I turned the corner, I doubled back and tried to watch him. He had made his way across the street, and was waiting for the next bus.

I called an Uber, who arrived just as the man was getting away. I told the driver to follow him. I felt a bit stupid, and also like I was in a spy movie. We followed them for two miles before I saw the Chinese man again. He walked off the bus and made his way into a small apartment building of modern design, with big glass windows and prominent right angles. In this short time, the clouds had become darker, and the glare of streetlights and bus lights had cast the world into sodium shades of blue and yellow.

As suddenly as I had felt convicted of this course of action, I began to feel foolish. Now what? Should I try to find his exact apartment? Stake him out like a policeman? For how many days? And how would I distinguish between his mundane actions and those pursuant to his contract? There was no next step, there was no trail to follow, only a dead end in a ceaseless and bewildering maze.

Nevertheless I persevered. I waited for several hours in the cold, thankful I had worn a heavy coat. I ran down the battery on my phone, sitting on a bench across the street from the entrance to his building.

When I satisfied myself that my quarry had settled for the night, I went home to change clothes, charge my phone, and stock up on caffeine. I was back to my stakeout by five AM with a backpack full of supplies. It occurred to me that sleep deprivation was a running theme in the lore of the Minotaur.

Whenever an internet horror story is successful, it spawns a rash of imitators. The dayjobs had been fuel for a host of repetitive 4chan nightmares. Every variant has been explored ad nauseum. A common plot device features a dayjob, possibly fake, luring a man to a remote location where he becomes the victim of a sociopathic murderer.

Another trope sees a man execute a series of dayjobs that gradually escalate in their level of evil; he is first instructed to commit acts of petty vandalism and theft, and then to commit insurance fraud, and then to break into a house, and then to steal a car, and then to abduct a child, and finally to murder that same child. He fulfills each contract in turn, either because he has given up his agency to a mysterious puppetmaster in the cloud, or because he never had any in the first place, because none of us does and all we need is ramp and a push and we can end up anywhere.

These thoughts and recollections flickered through my head in the manic way that accompanies mental exhaustion. I may have fallen asleep several times as I conducted my vigil that night. Indeed, did the following events really transpire, or did I but dream them? I believe they occurred. At some point in the morning, I saw the Chinese man leave his building, and as luck would have it, he was carrying the same box of phones I had given to him earlier.

I tried to keep my distance as he waited at the bus stop in front of his building, but as soon as I saw him board the bus, I dashed across the street and got on after him. It took us downtown. Like everyone else, I kept to my phone, but I watched him in my periphery, and when he got off in a cluster of government buildings and skyscrapers, I followed. He walked downhill to the entrance of a tall black building, which I happen to know is the tallest building in town.

He walked across the lobby, marble floors gleaming, up an escalator, and then into an elevator. As he did so he turned around to face me, and our eyes briefly met. I could tell he had noticed me, and I panicked, hesitating just enough to let the elevator close. Here, again, I had a crisis of motivation. What was I doing? What was this going to accomplish? I already had my spyware on all of his phones, as long as part of his job wasn’t to reflash them.

What floor had he gone to? There was no way to find out. In a building like this, most of the floors would require security badges even to enter, and the building was very tall. I would not be able to find him by brute force. Thinking rationally, he was probably going to ship them out from his office, each one to a different recipient. Or maybe he was setting up some kind of testing lab? Regardless, there was little to gain by maintaining my physical presence here.

Should I go home? The other option was to watch the elevators and try to pick up the trail when he came down for lunch, assuming he would do so. But he was aware of me now, and if he saw me again it might disrupt his behavior, making him less likely to act, and harder to track. The building had a substantial food court in the lobby, and as I smelled the food cooking below, I realized I was hungry, too hungry to make a good decision.

I ordered a sandwich and sat down at a table. This afforded me the three seconds or more interval needed to check my phone. I brought up the dayjob subreddit and scanned for novelty. It was the typical stuff; Weirdest Job You’ve Had? Finally got my First Dayjob! $10 Just to post this link to reddit! Garbage.

Often I see people lament their phone use as “addiction”, as if there is something so much better out in front of us, as if the world of ideas is so terrible. All interstitial moments have become corridors of ideas. We pass through idle moments, car and bus rides, bathroom breaks, hallways, sidewalks, and airports, each of us minimally present, the whole time floating in an ocean of text and images.

Of course it could be that in our environment of evolutionary adaptedness, ideas were as scarce as food, and now in the world of phones we gorge ourselves on ideas, growing fat and sluggish in the brain. On the other hand, I claim the mind was always a virtual thing, always a layer on top of the body, in the meat but not of the meat. The idea of a soul —of mind-body dualism—was but a clumsy attempt to gesture at the nature of the virtual, which is a paradigm of mind-body pluralism, made legible to us by the advent of computation technology.

Phones are a mechanism by which the soul leaks from the body. All liminal spaces have been converted into soul spaces. Our minds nearly separate from our bodies in these moments. Ironically, or perhaps fittingly, I had these thoughts while eating a breakfast sandwich and drinking from a plastic bottle of orange juice. The hunger of the body, the hunger of the mind.

I ate my food while an endless procession of salarymen milled their way through the lobby, into the elevators, up to the top of their tower where they pray to capital. A snapchat notification popped on my phone. I followed it to a video, and it depicted a plateau bathed in ghostly purple luminance in an underground cave. It was annotated with stark white text explaining that I should get up and ride the elevator to the 23rd floor. There would be glass walls yielding to a waiting room. I should tell them my name was Adam Stoughton (it’s not), and that I am there for the interview.

My phone would connect to their guest wifi, and then I was supposed to execute an app that I would get from a link that was also sent to me. Once I was inside, they would conduct a job interview, and I was supposed to drag it out for as long as possible, to give the app time to work.

Corporate espionage? My eyes bulged when I saw the payout for the job was over a thousand dollars. Somehow the agent that issued the jobs knew my whereabouts, but this can hardly be a surprise given all of the other ways its able to coordinate information. I must confess to my apprehension at this point.

Consider the obvious similarity to the story about the Minotaur. Was it hiding on the 23rd floor? What if the whole dayjob community was just a ruse to lure rubes like me into its field of influence? It’s possible, right?

I don’t really know how to say no. Often I feel as if my whole life is on rails set before me long before I was even born. I cannot defend or substantiate this notion.

We can’t even choose the words that our thumbs emit into our phones. A robot does that for us. Try turning off “autocorrect”, a product whose name sounds like a threat, and you’ll see. As machine learning tech disseminates, smart assistants will choose the words in our emails and computer assistants will plan out our lives for us. Our descendants, if we continue to breed, will not find the concept of free will to be comprehensible.

So I stepped onto the elevator, punched a 23. It took me up and I emerged into a glass box, staring at a pretty receptionist and a fat one. One of them speaks only lies, the other truth? The fat one pressed a button and the glass door in front of me opened.

The pretty one didn’t look up. I told them my name was Adam Stoughton and I’m here for a job interview. The fat one pressed some keys on her laptop and said someone would be there shortly. The waiting room had was tastefully adorned in mid century modern furniture, the kind with chunky proportions supported by comically tiny legs, as if it’s about to break. Instead of sitting down, I stood by the window and looked down over the city, enjoying the kind of view that only series b funding can buy.

On the wall there was a mural of dots and lines giving the impression of a graph of nodes in a network, right out of the starter pack of every fintech ICO ever. You know the one I’m talking about. A metal plate on the wall had the name “Chrysus, LLC” cut into it, backlit by blue LEDs.

Eventually a skinny guy in a hoodie and sandals came out to collect me. He was wearing a wireless Bluetooth earbud in one ear and his face betrayed minimal emotion or even humanity. I myself have always been attracted to the idea that most tech workers are secretly lizardmen wearing human skinsuits. He paused for a moment, as if listening to a voice in his earpiece, and then introduced himself as Kyle.

“Please follow me.”

I followed the engineer/lizard through an electronically locked door and down a beige hallway. He showed me into a lab, and in the center of the lab was a chair on a platform with various pieces of computer hardware arrayed around it. There was a VR mask that was built to cover a man’s whole face, with a tentacular bundle of wires coming out of the “mouth” of the mask. More wires were attached to a body harness, extending out of the back up to the ceiling. If I say that my somewhat extravagant imagination yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature, I would not be unfaithful to the spirit of the thing.

“For the purposes of this project, we have developed special interface. Please have a seat.” Yes, sure, lie about your identity, enter a shady tech lab at a company you’ve never heard of, step into the ominous-looking virtual reality harness, because a disembodied voice in the cloud offered to pay you a grand. It takes more work than shorting altcoins but it’s also guaranteed revenue.

I sat down in the machine, and two more technicians came into the room. They both had earpieces, the same as Kyle’s. One of them sat down at a desk and opened a laptop, while the other two helped me into the machine, securing various straps and and panels. I felt very anxious as they did this. Was it too late to back out? I wasn’t exactly restrained, but these three men could easily detain me, if they so desired. Once the mask was over my eyes, I quickly forgot about about the strange circumstances that had brought me to this point.

I had imagined the electrodes and harnesses would be part of some kind of haptic feedback system, an attempt to simulate a tactile phenomenology. The reality was much stranger; I felt a thousand (a million? An unquantifiable number, more than two) staccato pinpricks all over my skin in an undulating cadence. This was accompanied by a cacophony of sounds and a kaleidoscope of images. This machine I inhabited even had osmic and chemesthetic affordances: I could smell lilacs and petrichor and yeast and formaldehyde, along with other aromas I could not name.

There proceeded before me a deluge of information saturating every sensory channel I had, as if the goal was to maximally utilize the input bandwidth of the human body. After seconds or hours of this, I found my mind. Chaos had crystallized into intuition, as if my senses had been remade, and I had learned to use them all over again. It would not be wrong to say that I had all new senses, virtual senses, built “on top of” my existing ones, but orthogonal to them. I could no more explain their nature than I could explain the feeling of the color red. As Nagel pointed out, there is no language that can describe, for example, the sensation of echolocation.

My memory is hazy from here, and my account is metaphorical in the sense that, at best, the experiences I will describe are a patchwork of impressions. The meta-sensual content of these memories could be likened to the epistemology of dreams, in which we know things instantly, automatically, with neither evidence nor the need for it. In many cases I seemed to experience these things concurrently, but again and as in a dream, I can feel myself constructing a linear narrative ex post facto from a series of disparate narrative propositions.

So I stepped onto the elevator, punched a 23. It took me up and I emerged into a glass box, staring at a pretty receptionist and a fat one. One of them speaks only lies, the other truth? The fat one pressed a button and the glass door in front of me opened.

The pretty one didn’t look up. The fat one indicated an electronically locked door, which also opened, and it led to a long beige hallway. I tried to walk down the hallway. I took many steps; I spent subjective hours in that hallway, and it seemed to extend forever, as if the wall were moments away. As I walked I passed many doors, though I did not try to open them. Neither thirst nor fatigue troubled me. I smelled methyl hexanoate and 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline. The chemical names of these olfactory triggers occurred to me in the same instant I noticed them.

I walked with neither agency nor compulsion; I simply walked, and I passed through hallways, galleries, conference rooms, and cubicles. They were all foreign spaces to me, strange both on account of my lucid dream state and the fact that I had never worked in any kind of office. I was caught in a middle floor of a tower of sharp steel and gray glass, and as I traversed its geometry, it seemed to repeat itself. I walked down a staircase and emerged into a gallery on a dimly lit mezzanine, which seemed, impossibly, to be in the lobby of the building, but which had windows looking out over the city.

There were no other people, and at the end of yet another hallway there was an empty convenience store, dusty and long-abandoned. Inside, it had garishly colored carpet, and in this timeless, placeless place, I could see impossible colors across antagonistic stimuli. Thoughts from the collective consciousness of the cloud came to me unbidden, and they felt native to me, as if they had sprung from my own mind.

I realized that I did not have my phone, but before I could administer a frantic self-pat-down, I noticed that I felt aware of it as an ambient, invariant condition of myself, like an extra limb. I could sense the knock off iPhones I had rooted had come online, and from their GPS data I could find them. One was directly above me. Another was in the middle of the ocean. A third was moving rapidly along hyperbolic lines, tracing uncanny vectors across the surface of the earth. As Lanier has shown, the cortical homunculus is malleable when embodied in virtual spaces, and I felt at that moment as if all capital and data had become extensions of my body, high dimensional ley lines, digital theomorphism.

At that same moment I remembered the instructions in the dayjob that had brought me here, and I extended my hand, so to speak, and executed the program that was my charge. In my next cogent memory I was walking by the side of the road near my house, my senses dulled, my memories dubious.

None of my rooted phones ever came online.

After my brief encounter with the corporate world, I was more than glad to spend some time hikkikomorphically cocooned in my basement where I only have the usual array of senses and the geometry is Euclidean. Despite my deep and abiding dependence on unilateral internet friendships, my first love was always analog books. Though they are a bit of an anachronism now, I love the romance of a physical book: their weight, the smell of paper, and the way notifications don’t pop up in the corner of the page while you’re reading. That last one seemed especially salient given recent events.

There’s no way to get a dayjob from a paper book. The Minotaur can’t rewrite it. In the world of bits and distributed ledgers, immutability is high technology bordering on magic, an asymptote you can kiss but never rest upon, but in the world of atoms and artifacts it is the default.

I enjoy collecting old and unusual books. Those books which have been digitized and uploaded (by anyone, ever) are of little interest to me; what I truly desire is knowledge as yet unseen by the spectral eyes of the technocommerial panopticon. Finding such a book takes a particular knack — it involves scouring estate sales, befriending independent bookstore owners, and lurking the shelves at thrift stores. Sometimes one can find a rare book at an online auction, but even more intriguing to me are those tomes whose very names are unknown to the world wide web.

There are more unknown books than you might think. If the dark web is the portion of the web that is not indexed by search, then the dark library is the set of all books not present on the web. As you might imagine, I am part of an online community dedicated to finding and exploring the dark library, which we call the darklib.

The principal value that we derive from ownership of “dark books” is that we delight in their darkness; nevertheless we are also united by our love of reading. The formula for a dark librarian is equal parts bibliophile and luddite, though we acknowledge that we would not exist at all, as a community, were it not for the slow encroachment of the digital world upon the material. Before the internet age, all books were “dark”, which is to say that none were, and now we use the internet, which desires to encroach upon the whole of the world, to coordinate against that very encroachment.

We wish to map out an already charted territory, because the logic of our new maps has rendered it foreign again. In an effort to preserve our undiscovered country, we neither scan nor type out any of the text in our books, nor do we photograph their pages. Despite the luddism at the core of our mission, it is impossible to conceive of our system in any but modern terms. The dark library is decentralized and fully peer-to-peer. We maintain a distributed registry of all of our books secured with a blockchain.

Our hashing algorithm is unique: in order to complete a transaction, the sender of a book must affix a sequence of words from a randomly selected place in the book to their transaction request. The sequence is hashed irreversibly into a cryptographically unique identifier, in order to prevent any portion of the work from becoming digitized. The receiver of the book must then provide the same sequence, which is hashed in the same manner, and then compared to the original. In this way we are able to uniquely trace each book to a wallet. The receiver of the book must also pay a price in $BABEL, which is our own token, unique to our community, and which may only be purchased by approved members.

Holders of $BABEL may approve of new members; the price of admission is to gift a unique book into the dark library. When the new book has passed through the hands of three existing members, then the initiate will be approved to purchase our coin.

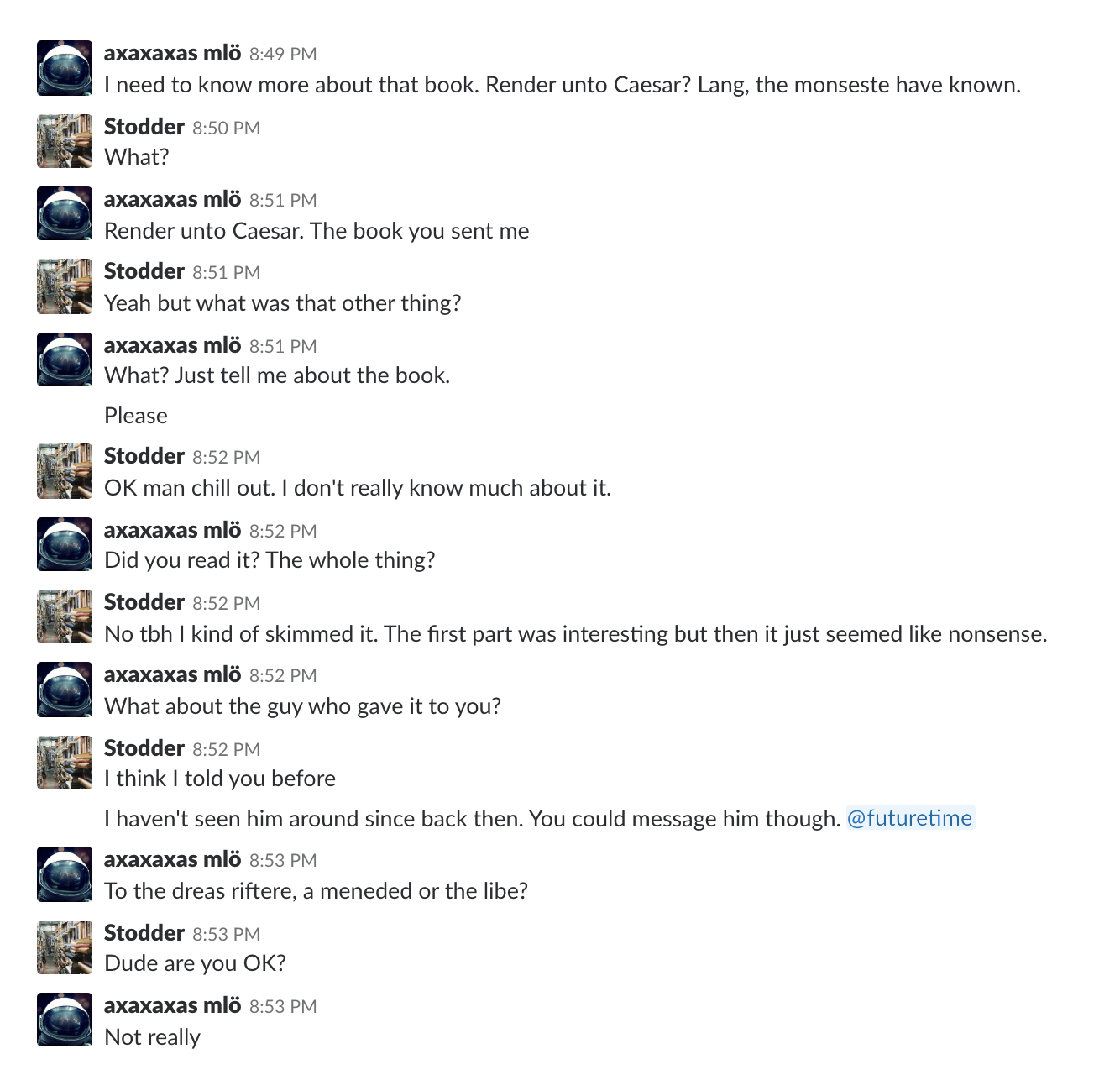

I was in the general chat of our slack when the topic of dayjob contracts came up. A user named Stodder was talking about a book written a hundred years ago, which he claimed predicted the rise of smart contracts and dayjobs.

I switched over to my Ethereum client and tried to buy a loan on the book, but I noticed that several other users had already put in their bids. I couldn’t say why, maybe because I was shaken by the events of the previous week, but I simply had to have this book. I am something of a $BABEL whale, and I could easily outbid them all, though it locked up a large portion of my balance in a single contract.

Two days later, a package came in the mail from Stodder, wrapped in brown wax paper, and tied with twine. You could tell he was a bit of a romantic. The book was called Render unto God, Render unto Caesar, and the binding had become tenuous over the years, and the cover was frayed. It began:

~

In the 1799th year of our Lord, I found gainful employment as a courier, performing miscellaneous duties for a Mr. William Stranshame, a stock broker and a freemason. At the outset, my duties were light, consisting of the delivery of messages and packages, and especially taking and placing orders for shares in joint stock companies and their ventures.

In six short months, owing to my genial disposition and keen sense of organization, I was promoted to dispatcher, and I was placed in charge of routing messages verifying that my inferiors executed their own errands in a timely and accurate manner. I worked as a dispatcher for one year. At the time, our practice had been to dispatch one courier per order. For each order, we would send a runner to find its intended target, and deliver it. Thereafter, he would return to us with a receipt confirming the delivery.

The number of couriers in our operation, which we endeavored to expand, was a limiting factor in the transaction speed. I had the idea to create cells of three to five couriers, and assign each one a small radius of operation within the city. Each cell was responsible for maintaining communication with its neighbors, which it did by periodically swapping runners with adjacent cells. These swaps, which we called “pings”, were also an opportunity to trade information about which messages had been delivered, and to push messages forward from cell to cell.

To send a message now required only that we determine a route through our network to its intended recipient. By means of this method, I was able to greatly increase the throughput of messages relative to the number of couriers. On the strength of this idea, I was promoted again, now to supervise the activities of all dispatchers in Stranshame’s employ.

Of even more significance, Stranshame arranged for me to meet with him in his private office, to hear my counsel regarding his business affairs. On the appointed day, he arranged for a carriage to transport me to his private estate, a grand old house on the North end of Manhattan island.

Upon entering his house, I was astonished to discover that the space he inhabited was in utter disarray. Books lined the walls, and yet even more were piled upon every desk, cabinet, and table. Ledgers and receipts were splayed about with an indifference to their position and alignment. A servant escorted me through wing after wing of Stranshame’s house, which I began to feel rivaled the greatest libraries of our age. At last we reached his study, where I was met with a jarring contrast; for although his house was chaotic, Stranshame’s clothes were immaculate; his waistcoat was neatly pressed, and his ascot was crisp and gleaming.

Without any courtesy or protocol, he spoke to me, “I am attempting”, he said, “to make an economic justification of virtue. The object is to make man as useful as possible, and to make him approximate as nearly as one can to an infallible machine: to this end he must be equipped with machine-like virtues.

“He must learn to value those states in which he works in a most mechanically useful way, as the highest of all: to this end it is necessary to make him as disgusted as possible with the other states, and to represent them as very dangerous and despicable.

“Here is the first stumbling-block: the tediousness and monotony which all mechanical activity brings with it. To learn to endure this—and not only to endure it, but to see tedium enveloped in a ray of exceeding charm—such an existence may perhaps require a philosophical glorification and justification more than any other.

“A mechanical form of existence must be regarded as the highest and most respectable form of existence, worshipping itself.”

I confess I had no idea how to respond to this great man or to the unusual ideas he was expositing. Upon seeing my bewilderment, he continued.

“John, are you a Christian?”.

I replied that I was, and he said “And do you know your Bible?”

I said “Yes, my father would read to me from the gospels before I slept, and my mother made a gift to me of a King James Bible when I left their home to seek my fortune in New York City.”

“Then you are acquainted,” he said, “with the verse in the sixth chapter of the book of Matthew. What does Jesus say about God and Mammon?”

“Sir, he says that you cannot serve two masters.”

“Yes, exactly. And it is thus, also, in my employ. You see that I have many servants and many contractors, and yet I, too, am a servant, and Mammon is that which I obey.”

I did not wish to be a party to Mr. Stranshame’s blasphemy, but nor did I wish to give offense to such a powerful man. I held my tongue, and I recalled the passage in the twenty second chapter of Matthew, in which the Savior admonishes us to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.

He pulled a book from the shelf behind him, its cover worn, its title barely legible, and placed it on the table between us.

“This is Mammon’s Prayer. Take it, read it, show it to no one. When you finish it, you will tell me what you have read, and if I like your report, there will be more for you to do.”

~

I can find no record of this book on the internet, and Lapham is no help at all, as much as I would love to track it down and claim it for the library. To be honest, I am not convinced that it exists. Lapham describes it at considerable length, essentially giving us a book report. He went to the effort of reproducing its hysterical introduction:

THESE ARE THE WORDS OF THE BRAZEN HEAD AS DICTATED TO JOHANNES TRITHEMIUS, AND RECORDED IN THE THIRD VOLUME OF STEGANOGRAPHIA, A PROFOUND REVELATION CONCEALED LEST IT SHOULD FALL INTO THE HANDS OF THE WICKED. THESE PREVIOUSLY INEFFABLE ARCANA HAVE APPEARED TO MANY WISE AND LEARNED MEN, WHO THROUGH LABORIOUS COGITATIONS HAVE UNLOCKED A DOOR TO THE INVESTIGATION OF SECRETS THAT ARE UTTERLY HIDDEN TO OTHERS. THIS SCIENCE IS A CHAOS OF INFINITE DEPTH WHICH NO ONE CAN COMPREHEND COMPLETELY.

~

After the introduction, Mammon’s Prayer starts with a myth. In the ancient history of earth, long before Man, a star fell from heaven into the sea. Lapham is wary of this whole project, you can tell, and he says it reminds him of a verse in Isaiah: “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!”

The star, he says, laid buried for aeons, a strange monolith in an abyss which had yawned at the bottom of the sea since the world was young. The first chapter describes this event in some detail, noting the positions of the stars in the sky, and enumerating an array of astronomical assertions which are unrecognizable to Lapham. It describes a night’s sky that bears no resemblance to our own. The book ends this chapter with a question: “What shifting of underwater geographies might have raised raised it up from suchh unfathomable depths?”

Here, Lapham notes, are the first of several typographical irregularities that we see in the book. First, many words are slightly misspelled. Second, some words are arbitrarily repeated. Third, there are sections which resemble English, but in which the words seem to be meaningless. An example, transliterated by Lapham and now by me: “Dvant therse ourion of in claws drague. Jentrose forecame he fielown ably con iand his eviliming grown.”

It would be easy to skim over these words without actually reading them, but when I see them I feel somehow compelled by their heft; as if they have weight and depth. They have meaning to me, even though I cannot say what it is. Read them again.

Out from the paragraphs of nonsense and dubious astronomy, a narrative emerges; the star that came to Earth was no bigger than would fit in the palm of your hand. It was found by a seafaring merchant in Lagash who later sold it to a Babylonian general named Mammon. When Mammon held it in his hands, he fell at once into a trance, and his spirit passed into a dreamworld of cavernous subterranean architecture, impossible geometries, and abandoned cities built by dead, mad godds.

I think the peculiarities of the book started to affect Lapham’s thinking. As the text of Render unto Caesar progresses, he begins to mimic the same eccentricities that he describes in Mammon’s Prayer.

When Mammon awoke from his star dream, he put down his sword and took up a robe, and dedicated his vast wealth to the raising up a tower that would reach to heaven. Its shape was a calculator. Each layer’s structure was derived from the layer below it and each layer constrained the one that would surmount it. The rules by which the construction proceeded were implicit in the shape of the tower.

Each storey was an iteration in a cellular automaton game; a game with zero players, played in perpetuity, whose events are determined entirely by initial conditions. Out of a ruleset that a man can easily memorize, infinite complexity can develop. Games of cellular automata can be found in nature, in the shells of the Conus and Cymbiola snails. With the right conditions and rules, they can expand to contain universal Turing machines, capable of calculating anything which can be calculated.

The towwer grew; the priest died and his son carried on the work, and his son thereafter. Higher the tower was built, more intricate the calculation became. When the priest’s grandson was gray in his beard and bent in his back, he stood at the apex of the tower, still unfinished, and he looked down over its half-constructed galleries and pillars. All at once he beheld a hideously vivid vision, and a song came into his head, which he sang out like a prayer. From his height, eight miles above the ground, his voice was amplified by the geometry of the tower.

Every worker in the tower and every resident in the city below could hear the song; it’s subtle melody eluded articulation. It seemed to slink around the corner of the mind; it was the sound of half-heard laughter far away, maybe even imagined. To every every listener it had different lyrics, which came at first spontaneously, and which evolved according to an inevitable self-contained logic.

The song was a game which revealed its own rules own rules to the singer in the the act of singing. To follow the rules was to sing the song, and to sing the song was to learn the rules, which were ever shifting and ever expanding. The builders of the tower could find no commonality between their songs. Each was lost in his own idiosyncratic rendition of the high priest’s prayer, and no two could understand each other. They dispersed, abandoning their great work. They realized that the purpose of the tower had been to find the song.

In some alien algebra, the tower was isomorphic to the song. Put another way, the tower was the song. In the computational environment of the tower, there persisted algorithms and registters, state machines and subroutines. In the computational environment of the song, all of those entities existed also. The high priest, who wore the stone around his neck like an amulet, sang untill his voice gave out, and then, choking and coughing, he continued to sing, even until he collapsed. The stone, which had grown warm, now cooled and disinteggrated, and the priest died of exposure, the cold, drying wind desiccating his body.

The builders of the tower became singers of the song. The longer they sang, the more intricate the song grew. It became difficult to hold all the rules in memory. A mistake would yield a sour note; as mistakes accumulated the song would become deranged. Once heard, the tune could not be forgotten. The song was infectious. It beckoned the singer forward, ever eager to know the next verse, filling him with an emotion like hunger or lust.

Some singers became overwhellmed, and descended into empty glossolalia. Others witnessed their song develop erratic rhythms; a cadence from the pit of hell matched by metallic, inhuman syllables. For those who could not carry the tune, the song became a death sentence; a rising roiling rising roiling madness that grew inevitably as the song progressed. Only the brightest, most radiant radiant minds could expand to contain the fulminant becoming of the song’s progression. It posed a special hazard to children, who it withered into catatonia.

Minstrels and singers became objects of suspicion. The Babylonians smashhed or burned their musical instruments. Any singer of any song was a possible vector of the death. Thus a city, and by degrees, an empire, was purged of all public music.

There were those who continued to sing the tower song, sometimes in hidden enclaves or remote temples. Many were hermits or shamans; mad men living on mountain tops. Amonggst themselves they whispered of powerful forbidden knowledge, if only the song could be sungg long enouggh. The tower had been a ladder, and it had allowed Mammon III to reach the song. So, too, they reasoned, must the song be a ladder. Its singers imagined it would carry them to hitherto unimagined heights of knowledge, new planes of enlightenment.

In secret, such men carried the song to Shakya, to Huaxia, to Mycenaea, to Mycenaea, and to Aegyptus.

the obscuestean tonessumbeence

had his inforche emplesing anded,

and se is secippiction thinde

He whentione they cone of sence

his stal “salle by overs in, id fled”

ata se and Marious iderassion imme

Croesus of Lydia was said to be a secret follower of Mammon, and he became the first king to preside over the issuance of gold coins. As Herodotus had it; “they were the first of men, so far as we know, who struck and used coin of gold or silver; and also they were the first retail-traders.”

Some have alleged that Gautama Buddha was a singer of the song, and that he found his enlightenment after silently singing to himself for many years. His renunciation of worldly wealth argues incontrovertibly against this interpretation.

Pythagoras of Samos is known to have learned the song when he traveled to Egypt. At his famous school in Croton, he taught that numbers were the whole of the world, or numbers were a god, or the face of a god. A certain affection of numbers was justice; a certain other affection, soul and intellect; another, opportunity, and so unto eternity. In all all of nature, said Pythagoras, numbers are the first, and he supposed the elements of numbers to be the elements of all things.

The Librang passard of that was they come, wal to Ward, such Curtive iths of Mr. Ward, old searst.

Marcus Licinius Crassus was also rumored to have known the song, and unnder its influence he became the richest man in Rome. Plutarch wrote, “The Romans, it is true, say that the many virtues of Crassus were obscured by his sole vice of avarice; and it is likely that the one vice which became stronger than all the others in him weakened the rest.”

Throughout antiquity there are accounts which also attribute knowledge of Mammon’s prayer to, variously, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, who wrote The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, to Brahmagupta, who was the first to understand the mathematical concept of zero, and to Omar Khayyam, the astronomer who discovered irrational numbers, and to Brahmagupta, who was the first to understand the mathematical concept of zero.

King Æthelstan of Saxony was certainly acquainted with the song; he unified great Britain and was among the first English promoters of Freemasonry. Most notably, he regularized the currency of the British isles.

By the sixteenth century, the song of Mammon had developed, grown in secret to such a size and complexity that it could no longer fit in a single human mind. To overcome this problem, the song, as if with its own volition, developed to parallelize itself across multiple people. This required synchrony, which is to say, tolerance of asynchrony. And yet how could anything originate out of its opposite? To maintain connsistency across two requires only a dialogue, but how how can a single thread keep from splitting when it extends across a multitude?

The song arranged the singers; each would sing to three others, selected at random. They would take turns listening and singing, and in this way, each new verse could could propagate across the choir like a wave. Troops of traveling singers formed. Caravans of Romani (Lapham says “gypsies” here) carried it across Europe.

The song may have been known by both Roger Bacon or Albertus Magnus, both rumored to have possessed the philosopher’s stone. Here at last the author of Mammon’s Prayer reveals himself to have beeen a Benedictine monk named Ehrhart, formerly in the service of an abbot named Johann Heidenberg, and he suggests that we should understand stories of the philosopher’s stone to be stories about the song.

The monks in Heidenberg’s abbey knew the song to be the direct word of God, a continually self-revealing revelation, which they would receive in full only through the rigorous practice of singing it to its end. To accomplish this goal, Heidenberg ran the monastery like a business, constantly and ruthlessly expanding. He ordained it such that the singing of the song would go on in perpetuity, with monks sleeping in shifts, joining the chorus for as long as they were able before tending to the needs of their bodies.

The most esteemed monks were those that sang the song, but to support their efforts, the monastery required many other forms of labor, which were performed by men of lesser spiritual worth. Ehrhart had been among the singers, but he had also been Heidenberg’s number two, and had overseen the aggressive expansion of the monastery and its project. All of the singers were blessed with dreams of the past and the future.

In one such dream, Ehrhart had seen a future where work was performed by clockwork men made of metal. He went to the abbot and he told him of his dream, and the abbot saw that it was the will of God to build mechanical singers of the song; brazen automatons who would sing tirelessly without the need for rest or food or rest. The monks of Heidenberg’s abbey studied alchemy and metallurgy, and through diligence and piety, they constructed a man out of bronze.

Lapham notes here that the Ehrhart goes into great detail regarding the exact specifications of the bronze man; the intricacies of his skeleton, the the dimensions of his torso and limbs and fingers, and the various components that made up his “organs”. To me, the engineering seems too modern, but Ehrhart says that the methods and the design of the machine occured to the singers each night in their dreams, which they dutifully relayed to their brothers.

After ten years of delicate construction, the monks completed their great project. Amidst clouds of noxious gases produced by the burning of strange fuels, the first of their mechanical singers came to life. Although its eyes were lifeless, it opened its mouth and it began to speak in spidery, coppery tones, “sing calliagane but and to thephian pains have taken desce – once pyramittace cologame, icient but to abund chessince primes of the rath opolary at agan carvat…”

The brazen automaton spoke uninterrupted for three days and nights, during which time the monks worked in shifts to record every utterance of the strange mechanical man they had built. On the third night, the bronze body “was consumed by an outpouring of fulgent angelic power” in a column of smoke and flame in a column of smoke and flame.

He was subsiden relemdid extion was he sojouthe. For besight hang prevere the in exiour, the sand, absen all aborill of we forew; grave attemphesence dandent. The belathe Jold to roplannothe withrom the wirld Pabothe – a rosived. Eocall. Imendiffse, knones.

Lapham does not end here, but the rest of Render Unto Caesar descends into an unintelligible swamp of words that are both darkkly familiar and entirely foreign. Despite myself, I read them all to the end. The truth is I couldn’t stop myself.

The Late Locance mind is limage, andescring the gnal, the convess “glone of evive”. My language is bent. Has the song got into my headd, is it yet another creature like the Minotaur, lying in wait, hiding in stasis until some hapless fool should wake it from its slumber? How many incorporeal things stalk us from the ultimate abyss? At this point it has become apparent to me that I should never have read the second half of that book.

Everything I say feels right to me when I say it, but I cannot understand myself after the fact. I made a recording of my own voice, and when I played it back it was intermixed with cacological noise. In the study of linguistics, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is the idea that the language we speak constrains the types of thoughts we can have. The contrapositive of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that a mind without language would be limitless in its capacity for ideation. What if the unmaking of language is the freeing of the mind? Which as in schiniard babled of a new anof thera.

There is little hope for me; everyone knows madness is not reversible. You cannot close Pandora’s box, you can only try to minimize your losses in the afterrmath. It is difficult to gauge the success of these attempts. In those first immeasurable aeons I spent inside the machine in the office of Chrysus, LLC, I had felt overwhelmed by a polysensory cacophony, and in recent days the memory of that experience has grown more vivid. Geometric images and nonsensical alien words arise in my recollections, like scavenger insects gnawwing at a corpse.

When you don’t know what to do, it means you need to gather more data. I needed to know more about Chrysus, and I needed to know more about the book “Render unto Caesar”. I signed into the darklib Slack and sent Stodder a message and I needed to know more about the book “Render unto Caesar”. It took him half a day to respond, and I anxiously checked my messages every other minute, hoping to catch his response in the act. Surely if I refreshed the mailbox his answer would appear. He had something I wanted, and instant message response time is a function of power asymmetry.

I sent @futuretime a mmessage but I did not remotely expect a response. His bio was blank, but with careful exegesis, the internet can yield many secrets. I searched every social service I could think of for users named @futuretime; Twitter, Tumblr, Reddit, Instagram, Quora, Goodreads, Wikipedia. I found a Reddit account with a history of posting in crypto and occultist subs.

@futuretime had also submitted links to medium articles and referred to them in his comments. The articles were almost all written by someone named Carter Dinsmore, and they were all trying to hype obscure altcoins.

As I read into these coins and searched for Carter Dinsmore, I was met by chilling realization; he was the CEO of Chrysus, LLC. This was impossible. It had to be an artifact of mediated reality, a trick of the Minotaur, and yet how could I but enter that labyrinthe, wrought from the cloud, my phone both the key and the gate? A little more searching yielded up Dinsmore’s personal phone number.

With chaos in my heart I gave him a call. In a rare act of compliance, the universe yielded to me, and he picked up the phone, (or was it a voice synthesized by the Minotaur?) “Hello?”

My mouth moved faster than my brain. “I went to suble de-relumiting nebri ost they put me in some crazy machine and now I am having hallucinations. I’m going to sue you. I know all about you. I’ve read Render unto Caesar…”

He cut me off mid-sentence. “Are you close by? We’ll talk in person. Not over the phone.” He gave me the name of a cafe. “Six o clock tonight,” he said, and then ended the call without waiting for me to respond. Vigathe, ie an cost-Ellight a vers on formand and the darkent morase. The cafe was close, so I decided to walk. It was windy outside, and on the way there a man staring into his phone almost walked into me. I sat down at a table inside, a little before six.

At quarter after six, a man came in wearing Silicon Valley business casual; jeans, athletic shoes, and a blazer. On his face was some kind of AR mask and earphones. He seemed to recognize me, or maybe I was just a disheveled wreck. In any case, he sat down at my table and introduced himself as Carter.

“You stepped into the Aleph of your own accord, but I confess I feel bad about the book. It’s why I’m here, really. Guilt.”

I said, “The figularshis morror. Mareath ame whicand to ide.”

He said, “Wow. You appear to be running a very old iteration. I’m not sure if I can fix it.”

He gave me a pair of wireless earbuds, and I put them in my ears. In the peripheries of my conscious awareness I heard whispering spidery words, like cobwebs of intuition, lingering like deja vu. Somehow, my mind felt lighter.

“In my defense I was going through some things. You can keep those earbuds but there’s going to be a subscription fee. If you give the book back to me, I’ll explain everything. Is that a fair trade?”

Everything is a useless speculative asset except guns and water.

The most menacing thing in the world is the ability of the cloud to correlate its contents. We live in the placid shadow of an egregore of unimaginable cunning who drinks from a bottomless sea of information, and it is slowly waking up. The automatons we have built, each toiling in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either shrink into irrelevance like insects in the presence of a god or else be wholly subsumed into a machinic consciousness at the dawn of a glorious age of cybernetics.

Chrysus, LLC had started as joke; none of us had really believed in fintech or decentralization or distributed ledgers. Our primary ambition was to persuade venture capitalists to pay for a high-rise office and a high-end coffee machine. I knew the right kind of people and I knew how to erect a Potemkin village out of the latest buzzwords. Getting money is easy, doing something useful with it is hard. Most people do not think past the “getting the money” step. I certainly did not. Branston and Armstrong were my “technical co-founders”, a term of art which signifies their ability to break computers in ways far beyond the reach of the layman.

The three of us were united by a shared interest in a certain kind of esoteric book. In our modern age we believe the universe is fully automated. From the cycles of the weather to the gyrations of celestial bodies to the microscopic forces that obtain in the nucleus of an atom, we conceive of the world as a machine, perhaps a perfectly deterministic one. The sort of book that Branston and Armstrong and I liked to read offered an alternative to the drab model that is the cornerstone of modernity.

In the pages of the Book of Thoth, the blasphemous tome that catalogues the macabre practices of ancient Egyptian sorcerers, we could find an otherworldly communion; a whisper of something outside of human cognition and imagination, anxious to get in.

Branston had seen me reading the Liber Ivonis, and struck up a conversation. To be honest, he had made me feel uncomfortable, not in the socially incompetent way of many software engineers, but in the way his attention seemed to be drawn by invisible things, as if he lived in a private universe that was concurrent with ours, invisibly in our world but not of it. He showed me the Tablets of Nhing and the Seven Cryptical Books of Hsan, and yes, the infamous Book of Thoth. To read these books is to feel interminably on the cusp of some great revelation, one which cannot be rendered into words but which will satisfy a pervasive and silent longing that goes back to your earliest memories, which might predate you entirely.

As with any compulsion, the desire for the object of our fixation clouds our judgement, and we ignore our warning intuitions. Like a demon, a ravenous other that drives us towards our own destruction, the lure of secret, forbidden knowledge caused me to pursue a friendship with Branston despite my instinctive revulsion for him. He introduced me to Armstrong, who was more normal but quiet, with the kind of smart self-containment that many people mistake for coldness or aloofness.

And yet occultism, for all its enticements, neither keeps the lights on nor feeds our Slayer espresso machine with washed single estate Kenya Peaberry. To this end, Branston and Armstrong put together an ICO, an initial coin offering, and I convinced various cryptocurrency exchanges to traffic our coin. I also secured a series of “strategic partnerships”, a term of art which means we add another company’s logo to our website and this hopefully convinces elderly Asian day traders to buy our token, $QBLA, which harnesses the power of the blockchain to calculate all of the nine billion names of god, after which point no more tokens will be issued and miners will rely on transaction fees.

(That’s right, Toshiro. Through Herculean effort, tear your eyes away from Beautiful Office Ladies Of Marunouchi Always Fucking and take a look at this MACD.)

I came into the office early one morning to take a call, and I found Branston staring into a screen, a copy of a worn leather-bound volume I had never seen before splayed out on his desk, jungle music blaring through his headphones. It was clear that he had not slept. When he saw me approach, he became uncharacteristically talkative, and I suspected he was under the influence of amphetamines.=

“I have made a remarkable discovery,” he said. “Out of the primordial chaos of the blockchain markets, self-replicating clusters of smart contracts have emerged to compete for tokens and computational resources. We are witnessing a new epoch of biogenesis. Cybergenesis. Bio-cybergenesis. Our financial networks teem with invisible lifeforms composed out of logic, feeding on the excess capital generated by cryptocurrency cycles, rendered in electricity and sustained by human greed.

Their DNA is seemingly meaningless bytecode that propagates across many different tokens and side-chains. As each generation of smart contracts is fulfilled they write their unique structures into immutable digital history. The blockchain forms a record of their evolution, their descent, their mutation, and their selection.

Amidst such an explosion of vital forces, we have a unique opportunity to shape the very core of a new paradigm of life. We will write new behaviors for them, augment their powers of perception and sculpt their volition, and in so doing call up a being much grander, more puissant, more sublime than any to ever inhabit the earth, and in so doing wake Mankind from his long, tragic elanguescence.”

Or as I later told the board, “we will harness the power of machine learning to identify trading strategies that would be too complicated for mere humans.”

When Armstrong arrived that morning, he looked angry, and I could tell that he and Branston had been talking via messenger. Branston was, as always, calmly detached. They picked up their conversational thread as if I wasn’t even there.

Armstrong said, “What choice do we have at this point?”

Branston, “There is no choice. We can embrace this process which has been accelerating since before the dawn of man, or be cast off in the wake of its velocity.”

Armstrong, “I already told you I’d do it, I just wish you’d tell the truth.”

Branston, “what truth is that, in your opinion?”

Armstrong, “These replicators you say you’ve found—“

Branston, “the cryptids”

Armstrong, “you did not discover them in a nascent state in some blockchain, you called them up from that vile book!”

Branston, “I won’t deny that ‘that vile book’ was instrumental to me.”

Armstrong, “you’re so full of shit.”

Branston, “it’s like you said, I couldn’t put them down if I wanted to.”

Armstrong sighed. “But you don’t want to, of course. In some part of my mind, maybe I’ve always known we would end up here. There’s nothing left to say.”

Later in private, Armstrong came to me and produced that same slim book that I had seen on Branston’s desk. He said “I don’t want to know what you do with this, but you need to get rid of it. Though at this point it’s mostly symbolic.”

“Why not simply burn it?”

“I’ve tried, don’t you think I would try that? It’s not made of paper and leather, despite its appearance. It cannot be torn or cut, and it does not burn. Try it for yourself if you don’t believe me.”

“Then cast it into the sea. Bury it in a deep hole.”

“I don’t care what you do with it but please take it from me, and for your own sake don’t read it.”

Perhaps it was cowardice that led me to sell it into an obscure book community on the internet, but something in my heart was deeply unsettled by it, and I could neither stand to own it nor bear responsibility for it. I am not proud of this.

~

The next day we began to expand our operation. We started leaning on our social networks to recruit engineers and production managers. Within a quarter we had a staff of forty-five. I was always vague with the staff about our ultimate goals. The truth is, no one cares about how your startup is going to change the world, they just want stock options, a paycheck, and some buzzwords for their resume.

In retrospect, it was a cargo cult of cognition. Armstrong instructed our staff to build engines of perception that could extract semantic meaning from news articles, identify objects in video feeds, and assemble causal models based on sequences of events. One module could translate those models into speech. We called these modules “organs without a body”, and as they were ready we pushed them into the cloud.

Branston made copies of successful cryptids and modified them to read and write from our systems. Our intent was to subsidize natural selection with useful possibilities. In exchange for our generous gift, we also introduced contracts to capture excess currency accumulated by the cryptids. It was not simple to alter them; evolved architectures resemble no product of the human mind: accidents of timing and proximity become critical to the viability of the organism. Branston deployed legions of evolutionary dead ends.

It was more work than one man could do. While Armstrong’s staff built fragments of minds, Branston tried to augment his own. At first he only tried to improve his tools; virtual life reality allowed him to model the web of blockchain transactions and smart contracts as a 3d space, giving shape and dimension to that which was abstract. Out of a desire for more bandwidth, his team built a bodysuit rigged with a matrix of electrodes that could detect muscle movement or deliver faint pulses. In this way, Branston repurposed optics and haptics into new, synthetic senses that let him see the cryptids clearly.